A Tale of Two Tunnels: The St. Clair Tunnel

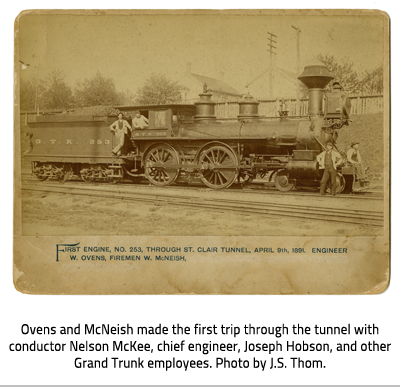

On April 9, 1891, Sarnia made headlines around the world. Steam whistles sounded on both sides of the St. Clair River as engine #253 made the first trip through the St. Clair Tunnel. The tunnel was an engineering marvel. Its construction captivated the world.

On April 9, 1891, Sarnia made headlines around the world. Steam whistles sounded on both sides of the St. Clair River as engine #253 made the first trip through the St. Clair Tunnel. The tunnel was an engineering marvel. Its construction captivated the world.

When the St. Clair Tunnel was built, railways did more than just move goods. They were an essential means of travel and communication. When people talked about “the cars” they meant railcars not automobiles.

The railway came to Sarnia in 1858. People and freight travelled by ferry across the St. Clair River at Point Edward before connecting with the railway again in Port Huron, Michigan. Loading and unloading the ferries was labour-intensive and time-consuming. The ferries battled strong currents, Great Lakes shipping traffic, poor weather, and winter ice. By the 1880s there was a continuous backlog of freight in the Point Edward yard.

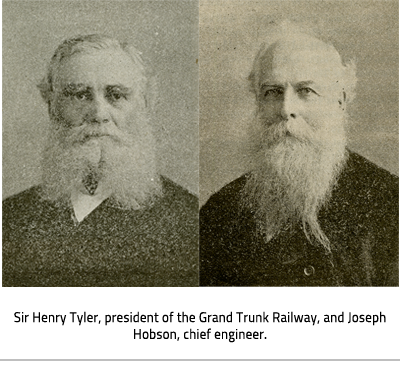

Building a rail bridge was impractical but building a tunnel was unprecedented. The thin layer of blue clay underneath the St. Clair River was soft and unstable. A tunnel attempt between Windsor and Detroit had failed. Sir Henry Tyler, president of the Grand Trunk Railway, recruited Joseph Hobson of Guelph as the chief engineer for the tunnel project. They chose a site downstream at Sarnia. After several unsuccessful tests, the only viable technique appeared to be shield tunneling. This method was pioneered by Marc Isambard Brunel beneath the Thames River in 1818.

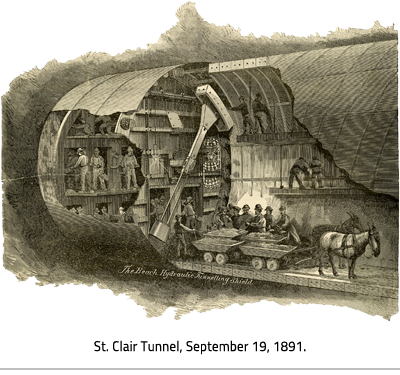

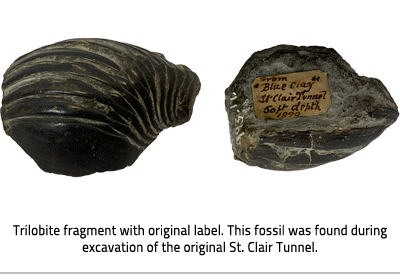

The shield method of tunnel excavation involves moving a steel shell (shield) through soft earth. Hydraulic rams force the shield along. The shield protects the tunnel heading from collapsing until a permanent lining is in place. The St. Clair Tunnel required two shields. They were the largest in the world. One started on each side of the river and they met in the middle. The tunnel was lined with cast iron and masonry. Within the shields were platforms and partitions to provide support and protect the workers. Workers performed back-breaking labour, digging clay and loading it into carts hauled out of the tunnel by horses and mules. Other workers built the cast iron lining behind the shield. The men worked in a compressed air environment. Moving in and out of the tunnel meant moving through several airlocks to avoid getting “the bends,” a potentially fatal condition associated with scuba diving. Despite these precautions, three tunnel workers died. Tunnel workers made 17.5 cents an hour.

The shield method of tunnel excavation involves moving a steel shell (shield) through soft earth. Hydraulic rams force the shield along. The shield protects the tunnel heading from collapsing until a permanent lining is in place. The St. Clair Tunnel required two shields. They were the largest in the world. One started on each side of the river and they met in the middle. The tunnel was lined with cast iron and masonry. Within the shields were platforms and partitions to provide support and protect the workers. Workers performed back-breaking labour, digging clay and loading it into carts hauled out of the tunnel by horses and mules. Other workers built the cast iron lining behind the shield. The men worked in a compressed air environment. Moving in and out of the tunnel meant moving through several airlocks to avoid getting “the bends,” a potentially fatal condition associated with scuba diving. Despite these precautions, three tunnel workers died. Tunnel workers made 17.5 cents an hour.

Tunneling began in the summer of 1889. The two shields met one year later on August 30, 1890, only ¼ inch out of alignment. The tunnel formally opened on September 19, 1891. Construction was a great success, although the original steam locomotives could cause deadly gases to build-up in the tunnel. In 1908, the steam locomotives were replaced by electric locomotives that ran through the tunnel along a high voltage wire. This eliminated the noxious gases. In 1958, aging materials and high maintenance costs forced the switch to diesel engines.

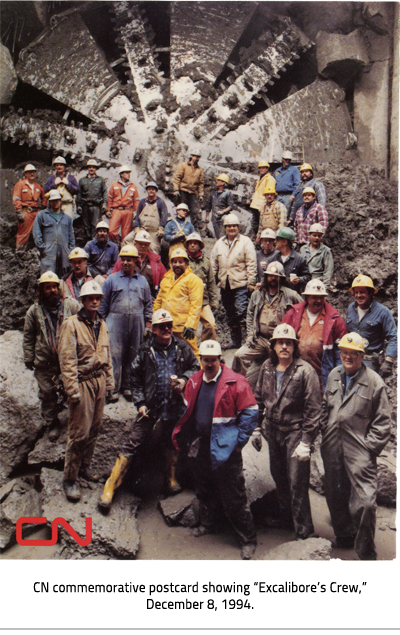

By the late 1980s, double stack container trains and multi-level auto carriers were too tall to fit through the tunnel. The diameter of the tunnel could not be increased so CN decided to build a new tunnel. The new, bigger tunnel was built 30m north of the original. It was dug from the Canadian side to the American side using an earth boring machine affectionately dubbed Excalibore. After the opening of the new St. Clair Tunnel in 1994, the original tunnel was sealed. The construction of the original St. Clair Tunnel brought Sarnia to the world stage. The project required ground-breaking shield tunneling technology, cast iron tunnel lining, and excavation in a compressed air environment. Today, this incredible accomplishment is all too easily forgotten – underground, out of mind.

By the late 1980s, double stack container trains and multi-level auto carriers were too tall to fit through the tunnel. The diameter of the tunnel could not be increased so CN decided to build a new tunnel. The new, bigger tunnel was built 30m north of the original. It was dug from the Canadian side to the American side using an earth boring machine affectionately dubbed Excalibore. After the opening of the new St. Clair Tunnel in 1994, the original tunnel was sealed. The construction of the original St. Clair Tunnel brought Sarnia to the world stage. The project required ground-breaking shield tunneling technology, cast iron tunnel lining, and excavation in a compressed air environment. Today, this incredible accomplishment is all too easily forgotten – underground, out of mind.

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page